NOTES

ON THE HISTORY OF TSINTZINA

©:

S.N.A., 2007

Contents:

1. timeline

2.

references

3.

short descriptions

4.

myth and fact

5.

the name “tsintzina”

6.

family info

7.

annex

1. TIMELINE

Part I:

Village Origins

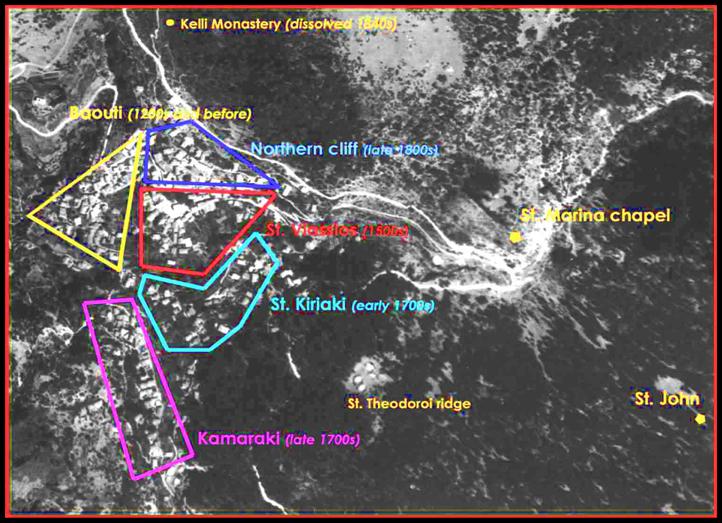

Stages of village development (best estimate)

Early village times remain unknown. Questions without a clear answer

include:

-

About when did first Tsintzina settlers appeared in the area

-

Their profession.

-

The exact location of first houses

-

Likely

other settlements around.

In

pre-historic periods, human presence in upper Mt. Parnon seems

unlikely. No remnants or tools were ever discovered. No evidence

either that until the end of the stone age, this part of Mt. Parnon

drew any significant populations. By contrast, its lower, western

slopes did.3

Byzantine & Early Ottoman Period.

Evidence suggests a continuous habitation of the surrounding area

from the 9th century A.D. (see also “myth & fact”

below).

St. Anargiroi Monastery (some 3 miles to the southwest) seems

initially built at that time.

The earliest known reference to Tsintzina –at least as location-

appears in a Byzantine Imperial Decree of 1292 or 1295 AD

6,7.

In another Imperial Decree

of 1416, the penultimate Emperor Theodore II Paleologos, specifies

details about taxation levied on the people of Tsintzina and

other nearby villages.

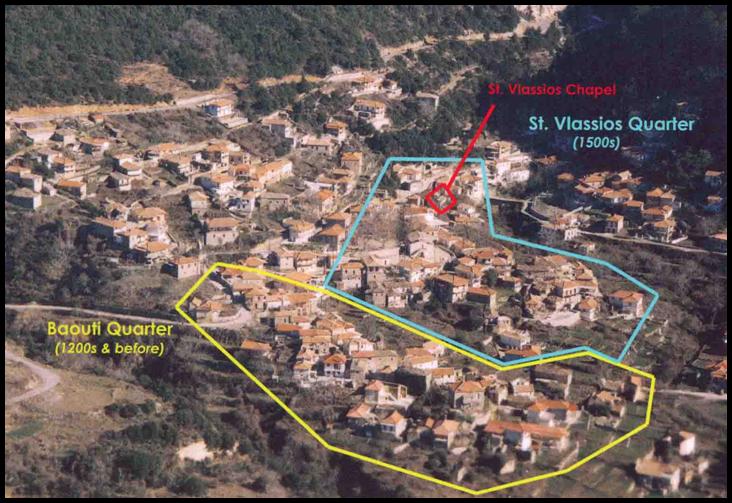

First Tsintzina settlers most probably resided in the Baouti area,

on the village southwest. St. Vlassios seems the first village

church, dating back to –at least- the 16th century.

Village partial aerial view from the southwest. In the red box, St.

Vlassios chapel, presumed first village church

(picture courtesy: S. Tseleki).

There are

virtually no official sources or references for the first stage of

the Ottoman occupation (1460-1688). For this period, there is

only a fresco inscription in the chapel of St. Vlassios, bearing a

date of 1611. The rehabilitation of nearby St. Anargiroi Monastery

is also recorded, between 1611 and 1622.

Picture 1: The

fresco inscription above the entrance of St. Vlassios chapel, with a

date of 1611

( courtesy of

Elias Constantakis)

St. Anargiroi

Monastery seems to have played a vital role in the area. Several

Tsintzinians joined its monastic ranks over time and a few assumed

senior positions.

In one of the

few surviving Monastic manuscripts, we read of the ordination of

Deacon Nektarios from Tsintzina, on July 8th, 1753.3

The Venetian Interval of

1688-1715 and the Grimani Census.

In 1688,

invading Venetians defeated the Ottoman occupiers of Southern

Greece. In a 1700 census -administered by Peloponnesus Governor

General Francesco Grimani- Tsintzina counted a mere 144

souls.

This census

is highly detailed both on people, animals and property. But the

figure of 144 Tsintzina could be an understatement. The impact of

late 17th century wars and a tacit avoidance –to minimize tax and

military implications- may not be ruled out.

Part II:

Village Consolidation

The second Turkish occupation

(1715-1821).

The Ottomans

reclaimed the area from the Venetians in 1715.

Evidence

suggests that this time, the Tsakones16

residents of Mt. Parnon reached a compromise with the Ottoman Turks

against the Venetians. As a result, after the Ottoman re-conquest,

the area got substantial commercial privileges as a reward.

In the coming

years, the area –including Tsintzina- became quite affluent. Some

accounts suggest a significant population influx in Tsintzina after

the early 1700s. Settlers came mostly from nearby Tsakonian

villages. A few persons or families seem to have come from much

further apart.

In the mid-1700s, the village

had a thriving production base. Textile processing (wool, linen

and cotton) and the construction of timber artifacts are well

documented. Relative village involvement in sheep farming and dairy

products trade is disputed.

Most of the timber and material

for textiles, was actually brought from outside. Processed final

products were traded mostly in the well-established markets of

Mistras (near Sparta) and Tegea (near Tripolis). This

pattern had resulted in some Tsintzinians settling already for good

in more faraway places.

Two French Travellers’

Tsintzina Memoirs

In late 17th

Century, two French travelers included Tsintzina in their Laconian

tour. Their travel memoirs were printed in Paris in the late 1670s.

The French

attempted a crossing from Mistra -via Tsintzina- to Monemvassia. The

description of the first stage of this voyage is of “a continuous

crossing through forested mountains, small water streams, some lakes

but mostly, numerous granite rocks”.

“A day’s

distance from Mistras [one] stations to the village of Tsintzina.

Its residents habitually make a point of welcoming strangers, hoping

to extract something. They usually stand in an observation point to

discover strangers crossing, whom they call by the blow of a

sea-shell to let them know that there is a village hanging on some

rock”.

On the French

text, territorial description and journey sequencing, often

correspond only vaguely to actual area details as seen today.

Presumably the account was written much later. In the meantime,

journey memories probably faded and the variety of locations

visited, obscured the accuracy of its recordings.

W. Leake’s 1806 Travel Notes on

Tsintzina.

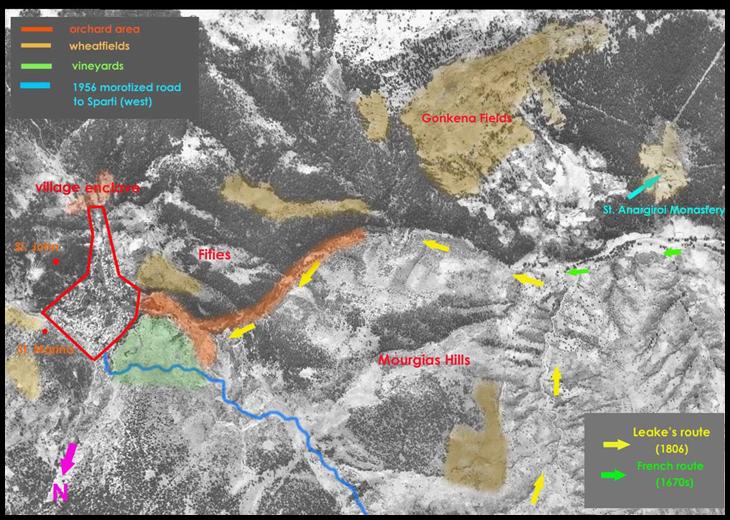

On March 22nd 1806,

British Army Officer William Martin Leake approached Tsintzina from

the western valley entrance. He observed NW village hills as being

full of narrow strips of vineyards. Other cultivations he recorded

were wheat, barley, maize, rye and grapes.

Leake asserts that the village

was populated by “80 families, in possession of substantial land”.

Further that Tsintzinians possess land and huts near Sparta and many

flocks which at this time of year grazed on the warmer low lands,

especially in the Elos valley (a seaby village some 50

miles south of Tsintzina and about 10 miles eastward of the port of

Gytheio).

Aerial

picture courtesy of C. Kimionis, Chania Airclub (Jan. 2007)

Leake also recorded that

Tsintzinians extracted timber (mostly oak and elm) from some

70 miles afar, on south-central Mt. Taygetos forests. And that they

traded significantly in cheese and other milk-based products.

Given Leake’s position in the

British Army, his remarks seem a good deal more accurate and

professional than the French accounts of the 1670s. Leake however

crossed the area rather quickly. He relied for help with his

muletrain of supplies from local guides and paid-up workers.

Therefore it is difficult to assess the extent his remarks are the

product of careful inquiry, or more of casual chat with locals along

the way.

Below: Reconstructing Leake’s & the French Travellers’ routes to

Tsintzina:

In

this 1945 aerial, the forest has not yet covered the Tsintzina

fields (abandoned mostly in the late 1950s). No car roads are

visible as the first one (reconstructed in the blue line) was

completed in 1956.

Leake’s initially southbound track (yellow arrows) gave him a

clear site of the large Gonkena wheat fields, abeam & on his right

(brown color). Later, with the village at sight, he could

observe the large vineyard area (green) on the slopes of

Koutsogiannena hill.

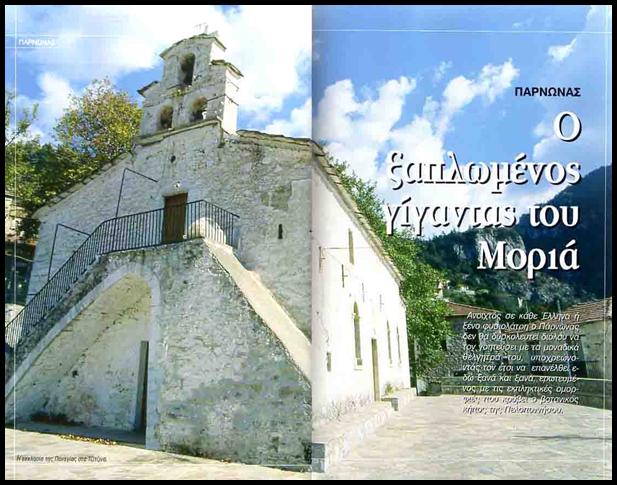

A New Central Church for a Rapidly

Growing Village.

Two months after Leake’s March

1806 visit, the village main church was completed. The building is

unusually large and tall. The Ottomans would not normally permit

religious structures of this size for occupied Christians.

It seems the church itself was

not built from scratch. Rather, a smaller chapel on location was

probably enlarged. A cemetery did exist at the time just off,

underneath the old village school square. The Tsintzina burial site

was later moved to St. Nicholas chapel, as it is today.

Tsintzinians worked with zeal

for the completion of the church. Its construction was supervised

directly by His Eminence, Iacovos, the Tsintzinian-born bishop of

Reon (the diocese Tsintzina belonged, based on Prastos town).

On the church cornerstone we also read that Iacovos, who

“…by Providence

happened to be a local, shaped the measures of the building,

supervising from beginning to end, by word, deed and funding…”

Above: Two-page spread of the village central church of the

Assumption (Koimisis) of Theotokos, as it appeared on a recent issue

of a Greek travel magazine

On bishop Iacovos’ last will

and testament of 1812, we have the first written account of the

Monastery of Kelli on the Tsintzina NW perimeter. This monastery was

dissolved a few years later, in the 1840s. Later, king Otto signed a

Decree of donating a plot that used to belong to the Monastery,

adjacent to the main village church, for the purpose of creating the

village school (a building completed in 1891, closed in the early

1950s and converted to a hotel in 1967).

The 1821 Revolution Against the

Ottomans

Various

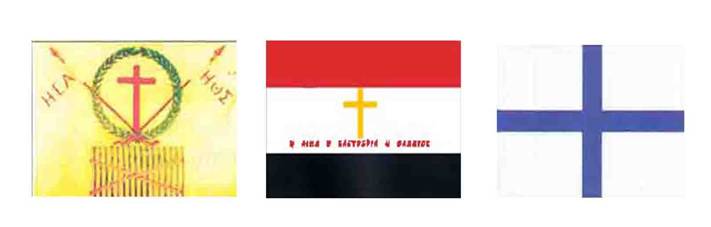

Greek Revolution Flags under which Tsintzinians fought in 1821-29:

-

Left, the “Friendly Society” flag with the initials “Freedom or

Death”.

- Center, Capt. Zacharias of Varvitsa (a nearby village) tri-color

flag: Red for blood, White for freedom, Black for death, as in the

horizontal inscription.

- Right: Gen. Theodore Kolokotronis flag (known in the West as “St.

Michael’s Cross”).

Tsintzinians appear to have

joined the revolution spontaneously and en mass, right from

its start. Early Greek successes had liberated all adjacent

territory by autumn 1821. After the successful conquest of Tripolis,

revolutionaries proceeded to forming local administrations.

Such developments allowed

Tsintzinians swiftly to claim ex-Turkish lands in the plains to the

east of the Sparta valley. In the process, civil strife broke out

with villagers from nearby Varvitsa in 1822. The quarrel was solved

via intervention from the central revolutionary Greek

administration, then based in Nafplion and Tsintzinians returned to

the battlefield.

Another bloody instance

occurred much later, in 1828. Tsintzinians clashed over land claims

with villagers from Geraki (a village some 8 miles to the East of

Zoupena). The battle was lost by the Gerakites who were

forced to concede the Tsilia estate to the Tsintzinians.

It appears that, in 1823,

Tsintzinians decided to form a solid battle unit, instead of joining

units here and there. Nicholas Gerasimos was chosen as their overall

commander after an open vote. This was accepted by Greek

revolutionary army officials and Gerasimos was given an army officer

rank.

Between 1821 and 1827 -when

Ottoman Turks and allies were largely defeated in the area-

Tsintzinians fought in battles all over the Peloponnese, including

Corinth, Argos, Kalamata, Navarino, Patras. They also participated

in the monumental conquest of Tripolis (then Turkish capital of

the Peloponnese) and in the epic battle of Dervenakia in 1822.

There, a few thousand Turkish troops sent in from Northern Greece as

reinforcements were trapped in mountain terrain and crushed by Greek

forces under Gen. Kolokotronis.

Two Revolutionary

Commanders under whom Tsintzinians fought at various battles.

-

Left, General Kolokotronis, the “Chief of Staff” of the

Revolutionary Army (portrait).

- Center, Kolokotronis at the famous battle of Dervenakia (where

Tsintzinians fought too)

- Right: Nikitas (Nikitaras) Stamatelopoulos, in a way “Commander”

of the greater Lakonia and Arkadia area (including Tsintzina).

Kolokotronis himself visited

Tsintzina at least once, in 1825. It was during the catastrophic

raids of Ibrahim Pasha, a Turkish ally from Egypt. Ibrahim arrived

in the Peloponnese with a significant Egyptian army unit to aid the

ailing Turkish forces. In a short while, he had reclaimed most of

earlier Greek gains. Kolokotronis and some of his officers stayed in

the mountain range between Argos and Tsintzina, where they regrouped

and expedited against Ibrahim’s troops.

Although not entirely clear, it

appears that the main Egyptian army did not -or was unsuccessful

to- expedite against the village itself. In September 1825, a

strong Egyptian force in search of food supplies was pushed back

after sustaining casualties, some 10 miles to the South West (off

the village of Vassara). On another raid, two separate Turco-Egyptian

units on a mopping-up operation from the South, appear to have

merged in Tsintzina before crossing Northeastwards. This is

consistent with verbal tradition that on skirmishes around Tsintzina

some of Ibrahim’s forces were killed by defending locals.

Tsintzinian Christos Andritsakis in particular, was said to have

successfully engaged at least one soldier below Psito, with

his bare hands.

During the Ibrahim raids,

Tsintzinians fortified St. John’s chapel with a strong wall. The

cave (including a separate, smaller one overhead), was turned

into a three-floor high “fortress” incorporating several gun-holes

and a water reservoir. Its strategic location on a steep cliff

overlooking the village, made it a safe shelter for most of the

local inhabitants.

These fortifications4

-on a chapel which on some accounts dates back to at least the 14th

century- were supervised by P. Economou and completed in 1826.

They still stand today as they originally were.

Below: 1826 fortifications at St. John’s Caves, during the Ibrahim

raids:

- 1.

Three-storey wall on the lower cave (where St. John’s chapel is).

- 2, 3. Ceiling-through walls on the upper & left (probably

auxiliary) caves.

In 1844, about forty-five

Tsintzinians are honored by the Greek government for their war

effort by an award of the “Iron Cross” and the “Copper Cross” for

one officer. In this list we read names from virtually all village

families.

Rapid Socio-Economic

Change Follows Independence.

In the first few years after

Independence from the Ottoman Turks in 1929, Tsintzinians

consolidated their earlier settlements of Zoupena and Goritsa, some

20 miles to the South. The area of Zoupena was particularly fertile

and suitable for olive growth, a notable nutritional shortage in the

mountain fields of Tsintzina. It appears that stronger and richer

families from Tsintzina (in particular the Koumoutzis and

Gerasimos, including their “clan-allied” familes of, for instance

Farmakis and Giannoukos ), were successful in securing a

dispropportionally large share of the best land around Zoupena and

Laina. Poorer Tsintzinian families, including recent migrants from

nearby villages, went to the much inferior lands around Goritsa,

which was mostly suitable for grazing and not particularly fertile

for agricultural use. Through a consistent effort, Goritsotes

managed swiftly to turn these kritsopia to numerous strips

where wheat and olives became a new source of wealth.

With King Otto’s 1835

administrative reforms, Goritsa and Zoupena –largely part time

settlements at the time- were incorporated into Dimos

Therapnon. Tsintzina, with a recorded population of 1,021 formed

separately the Dimos Parnonos. Nicholas Koumoutzis was

probably its first Mayor, as seen on a timber permit with a date of

1838.

The 1841 census recorded a

Tsintzina population of 1,344 which had risen to 1,532 by 1861.

Neigboring Agrianoi & Zarafona

villages formed Dimos Kroniou. This arrangement was

short-lived. All three above “Dimoi” merged to Dimos Therapnon in

1840 with a then census of some 3,750 people.

It appears that by 1844,

Tsintzinians had abandoned the village as yearlong residence. They

had firmly decided to reside in Goritsa and Zoupena between October

and June, much as it happened since and until the 1980s. The Goritsa

parish was officially incorporated in 1851. The foundation stone for

the grand Goritsa church –a sizeable renaissance building bearing

strong similarities with the Sparta, Tripolis and Athens cathedrals,

being also about the same size- was laid in 1854. The building

itself was completed in 1861 and some years later the two belfries

were added.

By the 1850s, the migration

current to Egypt was well under way. It was more than facilitated by

the catastrophic vendetta which raged mostly in Zoupena. The

vendetta concerned the old “aristocratic” family of Koumoutzis and

the Gerasimos family.

The Koumoutzis family was

perhaps the most prominent and well established to date. It held

center-stage in village affairs and a considerable amount of

political authority, dating back to -some say- the pre-Turkish

conquest era. On the other hand, the Gerasimos family had gain

significant military clout during the revolutionary period. Since

then, they had benefited mostly with a tacit alliance of Nicholas

Gerasimos with the influential Giatrakos family of Laconia.

The exact cause of the vendetta

is unknown. It lasted for several years and resulted in at least a

few violent incidents and a substantial exodus from Zoupena. The

village itself remained largely divided, as some families sided with

the Koumoutzis and some with the Gerasimos.

In 1873, Christos Tsakonas, a

Zoupena Tsintzinian who had already migrated to Egypt, attempted to

move to America. Upon arrival in New York, he became impressed by

the New World. Two years later, he was already established

well-enough to return to Greece and persuade other villagers to

follow.

This, since 1875, a steady

annual migration trickle begins from Tsintzina to America. It soon

spills over to the greater Sparta area and by the 1890s, has already

reached an extent which alerted the Greek government to try

–unsuccessfully- to stem the tide. Before the turn of the century,

Tsintzinian Americans amounted to several hundred and had become

particularly well established, mainly in the Midwest and mostly on

the fruit trade and later, on the candy and ice-cream business.

Next - references |